2012 U.S. Olympic women’s quadruple sculls team, training/rowing on Carnegie Lake, Princeton. The Boathouse that they row out of and train at is Princeton University Boathouse. June 23, 2012

On Aug. 7 at 11:30 a.m., Hunter Kemper will jump into the water in the Serpentine, the famous lake in the former royal hunting ground in London now called Hyde Park, for the start of the Olympic triathlon. His heart rate will quickly whomp-whomp, whomp-whomp up to 172 beats per minute as he and the other 54 contestants start thrashing their way down the swim course. The 6 ft. 2 in., 175 lb. (188 cm, 79 kg) Kemper, 36, will sustain that heart rate over a 1,500-m swim followed by a 40-km bike ride and a 10-km run.

It is anything but a walk in the park. His goal is to “maximize my output that day,” which is to say suck up an hour and 48 minutes of pain. “That’s very hard to do,” he says. “Sometimes we shy away. It’s so painful, you think, I can’t go another minute.” But he will.

On Dorney Lake, near Windsor Castle, rowers in the U.S. women’s eight boat will be thinking along the same lines. In their 2,000-m race, these powerful women, on average over 6 ft. (183 cm) tall and weighing about 175 lb. (79 kg), each will be doing the equivalent of 200 intermediate cleans — lifting a barbell from knees to chest — while simultaneously doing leg squats. They will be sucking in three times the oxygen that most of us do and converting far more of it to muscle power. “You start out with a flat-out sprint, and 40 seconds into the race you are like, Oh s—, I’m not going to make it,” says Esther Lofgren, part of the current world-champion eight. “Luckily, we’ve done it before.”

(PHOTOS: Ralph Lauren’s U.S. Opening Ceremony Uniforms)

In the men’s marathon, Kenya‘s Wilson Kipsang — a physical engine perfectly proportioned to run long distances rapidly, with long, thin legs and a huge heart — will set a pace that looks graceful in its economy: about 4 min. 45 sec. per mile over 26-plus miles, a speed that will destroy most competitors. The Kenyans live and train at 8,000 ft. (2,440 m), in the highlands of Africa’s Great Rift Valley. Living high confers advantages in endurance, like more oxygen-carrying red blood cells. Lots of runners go there to try to match the Kenyans’ rigorous work habits, but few can match them on race day. The best U.S. marathoner, Meb Keflezighi, is a transplant from that region.

Are the Kenyans and Ethiopians the fittest people in the world? Or is it the tall, toned rowers ripping through the water toward the finish line? The wiry triathletes can certainly compete for the title, not to mention those relatively small — compared with rowers — leg-and-lung machines known as cyclists. Last year’s Tour de France winner, Cadel Evans, weighs 141 lb. (64 kg), perhaps the perfect weight for pedaling up an Alp.

All the athletes who qualify for the U.S. Olympic team are fit. Boxers, taekwondoers, wrestlers, gymnasts, swimmers, sprinters, cyclists, fencers, archers and trampolinists do not get a ticket to London because they’re just in pretty good shape. And the winner of the decathlon claims the honorary title of “world’s greatest athlete.” But fitness at the Olympic level takes on a different meaning. “Everybody’s looking for an edge, and the edge comes from making sure you are competing at all aspects of performance: biomechanics, the mental, nutritional aspects,” says Chris Carmichael, who has trained dozens of Olympians, including George Hincapie and Ed Moses. “At the Olympic level, they are looking at performance vs. just being fit.” The fittest athletes don’t always get the medals. But they will always have a critical advantage.

The Science of Fitness

the pace begins at an easy 7 min. 30 sec. a mile, a clocking any dedicated runner could manage. At the U.S. Olympic training center’s performance lab in Colorado Springs, athletes hop on a treadmill — or a stationary bike if they’re cyclists — wired to instruments to measure their performance. Gradually, the pace quickens until the athlete can no longer bear it and hits the red stop button, exhausted.

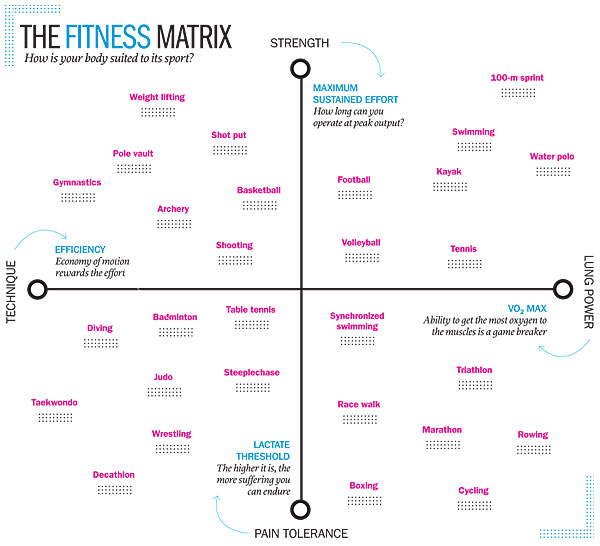

The physiologists work on four measurable components of fitness: VO2 max, lactate threshold, economy of motion and maximum sustained output. Biomechanics are important in that the less energy an athlete expends in a given movement — a swimming stroke, say — the more will be available for peak output. There are unmeasurables too, like the mental aspects of training and competing — one reason every Olympic team employs sports psychologists.

Scientists and trainers in Colorado Springs avoid the word fittest as it applies to their athletes because of the different requirements among the sports. “It’s not one size fits all,” says Rob Schwartz, strength and conditioning coach for the combat sports such as wrestling and boxing. “There are several parameters of fitness, whether it’s strength, power, flexibility, coordination, agility or kinesthetic awareness — can you feel what you’re doing in space.” But all bodies have hearts, lungs and muscles, and maximizing their output is clearly a feature of fitness. The U.S. Olympic Committee’s physiologists have calculated the difference between gold-medal glory and fourth-place hard-luck story (oh, you were at the Olympics?) as one-half of 1% on average — .005. “Our goal is to squeeze that critical one-half of 1% out of Team USA athletes,” says Randy Wilber, a senior sport physiologist at the Colorado Springs training center. That difference could be delivering a small amount of additional oxygen to straining muscles or a little less lactic acid. Fitness can account for it.

If your body is an engine, VO2 max measures its displacement. VO2 max measures milliliters of oxygen per minute per kilogram of body weight, converted to a percentage. The higher the number, the more oxygen you’re getting to your muscles. Most of us can hit 50% on a good day. Top college athletes clock in around 75%. Elite U.S. cyclists are in the 82%-to-85% range, but they’re using only their legs. (Lance Armstrong cracked 90%; believe what you want about his alleged drug use, the guy has an indisputably massive engine.) The highest rate Wilber ever measured was 91%, in a Scandinavian cross-country skier whose heart was chugging like a locomotive at 197 beats per minute.

Scientists used to think VO2 max defined fitness, but men and women who can’t crack the top VO2-max scores still reach the podium with regularity. So the focus has broadened to the lactate, or anaerobic, threshold. If you’ve ever been running or swimming a race and found yourself in so much pain that you couldn’t go another inch, that was your lactate threshold paying a call. It happens because lactic acid and positive hydrogen ions form in the biochemistry of exercise and interfere with muscle contraction if the lactic acid can’t be removed quickly enough. No contraction, no action.

(PHOTOS: The Host Country: Scenes from Modern British Life)

Most sports can be characterized as either aerobic or anaerobic. Sprinting is anaerobic; the distance is too short to get oxygen pumped down from the heart. You just drain whatever’s in the leg muscles. Wrestling is too. Cycling and distance are aerobic.

Rowing is both an anaerobic and an aerobic sport. In a 2,000-m race, the initial 250 m is a flat-out sprint in which the rowers generate energy without much oxygen flowing to their muscles; the middle 1,500 m is aerobic as their hearts push the oxygen in their bloodstreams to their legs and arms. But as the boat nears the finish line, those sinews will no longer be able to clear the lactic acid that’s been building. The acid levels will peak at about 20 millimoles per 100 ml of blood. That’s when the painfest begins. “When you get to 20, you are in never-never land,” says Fritz Hagerman, the eminent exercise physiologist at Ohio University who started the first U.S. Olympic performance lab in 1977. “You wish you were dead, and you are afraid you won’t be.”

Fitness, as every gym teacher told you, is a function of pain. For wrestlers, it means enduring 30- to 90-minute nonstop “grind” matches, to be able to deliver more pain and fatigue than they’re taking in. “Wrestlers use the term break your opponent,” says Schwartz. The fittest athletes have dialed up their lactate thresholds through training designed to do just that. The more lactic acid your body can process, the more power you get out of it and the longer you can continue. Rowers use an ergometer to measure power output expressed in watts, which is converted to a 2,000-m time. Since her college days at Harvard, Lofgren has improved her erg score by 15 seconds. Fitter also equals faster. “A boat length is about 3 seconds,” she says. “If your erg score improves 15 seconds, you are five boat lengths better.”

Reaching Olympian fitness requires a training regimen that’s not available to part-time athletes. Want to row on the U.S. women’s team? Better be ready to stick an oar in the water at 7 a.m. for two hours on a daily 10,000-m to 12,000-m endurance row. Then you can have breakfast. At 11 a.m. there’s an hour of weight lifting. Then more food and rest. At 5 p.m. you’re back in the boat for a two-hour, 8,000-m row, working on technique and power. You will need to consume 5,000 calories a day. You will sleep well. At the USOC’s Chula Vista, Calif., training center, Lofgren, 27, says track athletes — no slouches themselves — were teasing the rowers over their insane workouts. “They were telling us that we chose the wrong sport,” she says.

That’s definitely not true of Lofgren. Genes matter. They determine ultimately how fast or strong you can be. Everyone is born with a mix of fast-twitch, slow-twitch and intermediate-twitch muscles. If you don’t have the right combination of fast-twitch and intermediate-twitch muscles in your legs, you won’t ever be fit enough to be a sprinter. Slow-twitch muscles can’t be trained to become fast-twitch muscles, although the converse is true. Lofgren’s parents were both elite rowers, meaning she was more likely to have more of the slow-twitch muscles conducive to rowing.

She may also have inherited her parents’ work ethic. For top athletes such as Lofgren and Kemper, fitness is a six-day-a-week job. Kemper, a father of three, lives in Colorado Springs to train at altitude; he’s been a professional since 1998. He starts at 7:30 a.m. with a 5,000-m swim. He swims first not because it’s the first event in his sport but because “it’s the hardest thing for me to do if I’m tired.” After a break, he runs 10 to 12 miles (16 to 19 km), then knocks off for lunch. Then he’s on the bike for a couple of hours, pedaling 200 to 240 miles (320 to 385 km) a week. And don’t forget a couple of hours of weights and stretching each week.

It’s sometimes difficult for superfit athletes like Kemper to taper off in the weeks before a big race. “You don’t want to get to a race and say, ‘I could have used two more days of training.’ You don’t want that to happen in London,” he says. So he’s made sure he’s put in the mileage. Despite all the science, nutrition and exercise machines, there remains a simple formula for becoming an Olympic champion. The winning athletes are simply willing to work harder than anyone else to reach their goal. “You don’t win an Olympic medal by being gifted,” says Carmichael, the trainer. “You win an Olympic medal by working your ass off.” There’s something very sporting in that.